Kusheda Mensah's modular furniture puts the fun in functional

The British-Ghanaian designer talks building community, growing pains, and collaborating with Hem

Watch This Space is a franchise spotlighting design stars on the rise that are in my orbit

Way back in 2021, I posted a photo of Kusheda Mensah on the @spoiledg00ds account. I was captivated by the playful form of these sculptural poufs that bloomed within a floral backdrop created by Michael S. Smith for de Gournay. The Mutual collection was conceived during her final semester at University of the Arts London where she studied surface design. But as she struggled to establish the infrastructure to mass produce these abstract masterpieces, the designer was presented with an opportunity to fulfill another dream when she gave birth to her son, Sior in 2021, followed closely by her daughter, Soleil in 2023. After spending the past four years fully locked into her role as a full-time mother, Kusheda quietly returned to the design scene in 2024 for an exhibition at Harewood Biennial.

So as you can imagine, I was over the moon when she unveiled the Palma Pouf series in collaboration with Hem last week. A release that has been two years in the making, it all started with a DM from Petrus Palmér, founder and CEO of Hem. With this new partnership, Kusheda is also making history as the first Black woman designer on the Swedish brand’s roster since it was established in 2014. “Hem was always on my vision board of places to start if you ever wanted to scale up or have a commercial product out—that was where I wanted to be,” she says.

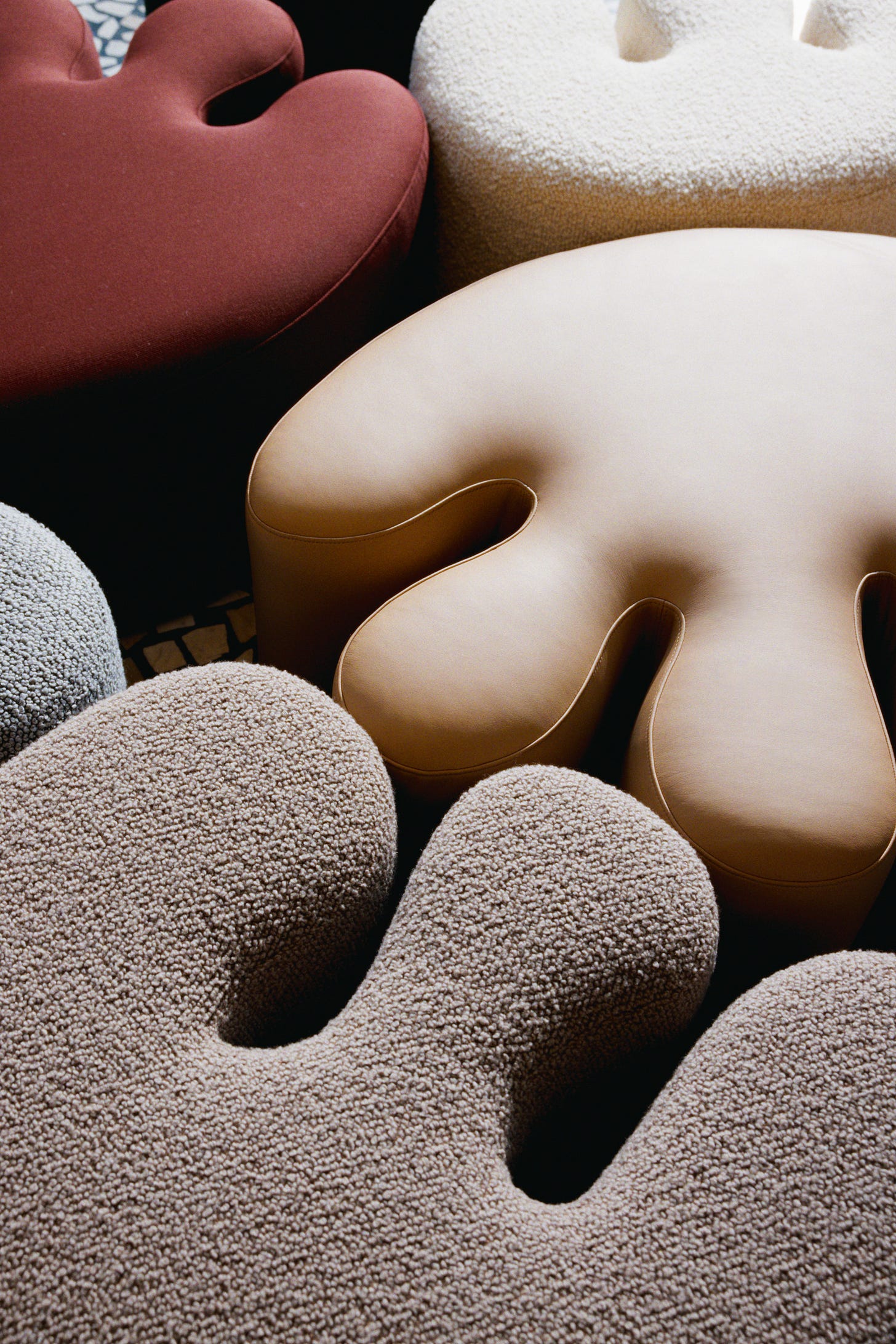

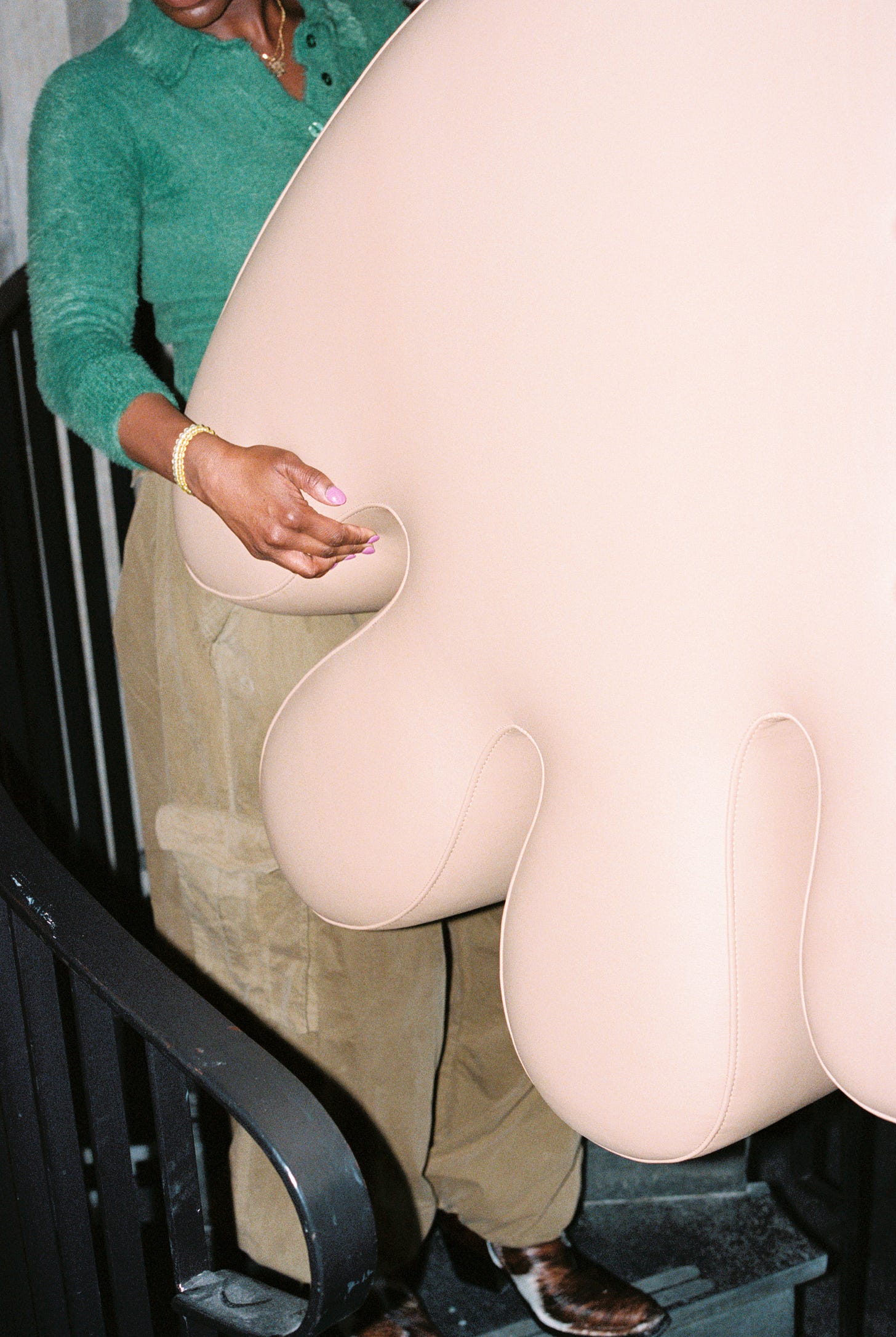

Palma is available in three shapes with a number of upholstery options starting at $899—Kusheda strongly encourages people to use the poufs for perching, parking, and lounging. “It’s quite a nice add on to the sofas you may have in your house,” she adds. “It’s a pouf with some personality, but also has an artistic, conceptual thing behind it that exists. It’s this product now that you can have forever.” While I envy everyone that will get to see these statement pieces showcased this week at 3daysofdesign, Denmark’s annual design festival in Copenhagen, I’m grateful that I had the opportunity to speak with Kusheda. Consider this interview as an invitation to further engage with her interactive work and learn more about how she’s creating a legacy built on a communal sense of living through playful forms embedded with cultural context.

Can you recall your earliest design memory?

Kusheda Mensah: When I’m asked this question, I always think about my mum. Ghana was considered the land of gold so she’d always collect lots of gold jewelry. There’s a symbol called Gye Nyame and she had it on a ring. Whenever I was holding her hand that was the thing that I would hold on to, I’d be looking at it thinking “What does this symbol mean?” Then I started to notice that it appeared on fabric that she would wear. That’s my first design memory because it was more textile based—I studied print design, I wouldn’t even say as a result, it felt like a default because it just exists in my heritage. I’ve been wanting to go back into textiles now and take it more seriously. I do find that I’m like, “Oh my God, can I actually do it justice?” because it’s me telling my story, but there’s so much more lineage behind me. That’s actually so much pressure. I find myself procrastinating, but I’ll get there.

You studied surface design at University of the Arts London. Was there anything that informed this path for you to pursue?

KM: I always knew that I had a creative brain. I initially went to school for fashion design and thought that’s what I wanted to do. I was so driven to do that and then when I started school, I loved the shape of things but hated creating patterns for garments. That’s the one thing I really remember hating, I couldn’t get my head around it. One of my tutors always said I should have been a typographist because I was really obsessed with text and the shape, and I was like “No, fuck you. You don’t get my dream!” And my mom definitely didn’t get my dream, she was an African woman who wanted me to be a doctor or something stable.

I went into fashion design, but then I dropped out because I was like “I don’t know what to do with all these skills I’ve acquired.” I paid for all of that and didn’t know where to put all this energy. I took a year off and then I met someone working in retail who was doing that [surface design] course and thought I’d try it. I didn’t even think it would manifest into this… I wish I could get that time back, you definitely take it for granted because you do not have that kind of access [post-grad]. The amount of money it costs to even make any of this stuff—as a student, you get a discount. Now, you get nothing. There is definitely something to be said about just sticking out the course. You can drop out and do your little thing on the side, but the advice people are giving out on this doesn’t work for everyone.

Your debut furniture collection debuted at Salone Satellite in 2018 which feels like a very different time... From your POV, how has the industry shifted over the past seven years?

KM: I think we’re more open to seeing what people around the world are doing as opposed to just what white women and men in design are doing. There’s a lot more information, a lot more of “This person is doing this, but what’s that other person doing?” This concentrated amount of time [during the pandemic] made people slow down and stop and see what was more important. People are more focused on the beauty that they want to create and not just churning out lots of stuff. There’s more urgency to create things for a communal sense of living and pushing more interaction where there hasn’t been before the pandemic. During the pandemic, we weren’t physically able to be together. Design is looking at how we can bring people together. I mean, that’s what design is anyway, it’s for people. I don’t think that’s necessarily changed, maybe just amplified a bit more.

Why is sustainability an important aspect of your practice?

KM: I think about sustainability in lots of different ways. For me, it’s about durability and longevity. I only speak about it because there are certain things that are pedaled through and people just jump on something and they’ll go for it. For example, I did a project with the V&A highlighting how leather can be used; Gen Z is being pushed with this message that vegan leather is the best, like this is what we should be using, but it’s not because it’s plastic. There are lots of different materials being developed to emulate the same thing, but this is still manmade, whereas leather is a byproduct of the meat that we consume. So actually what we should be thinking about is how we consume meat, not the leather itself, because the leather is always going to exist. If we didn’t do anything with it, it would still be causing carbon emissions, so it’s about how we use materials.

I work with chip foam, which [consists of] lots of recycled bits—the material itself isn’t the most sustainable, but in terms of longevity and durability it’s going to stand the test of time. All the vintage items that we’re buying now on websites like Pamono, the longevity is there. That’s how I look at sustainability, through materials. It’s really important. You might need the next IKEA thing, but how can you make it last and how can that thing evolve with you? That’s how we should be looking at the world. Like, how can we make use of things we have and not throw them away?

Your pieces put the fun in functional, but there’s a deeper intention beneath the surface. I love how your vision of modular furniture is about building connection and mutuality between people.

KM: Part of my ethos and why I create quite dramatic shapes is because people are so drawn to it and then they’re like “Can I touch it?” It looks really expensive, but no, put your feet up! That’s the vibe. It’s supposed to have that tactile nature that invites you in. It builds this social space that draws people in and then they want to gather. It’s quite conceptual because it’s just furniture, but when I debuted the first collection in Milan I didn’t even think that people would really understand what I was saying or envisioning doing. What I really wanted was to create a gigantic social experiment [of] people gathering in this huge park [and] pushing all the outdoor furniture together and communing. People really understood the concept which I know it’s not really hard to understand—furniture can do this.

What are some of your references or inspirations for the shapes?

KM: My first iterations for designing it were body parts like the shape of a face. It was supposed to be a 20-piece collection so it started out as body shapes—I had drawn something that looked a bit like an elbow and an arm, and then whatever fit into that was organically drawing crazy shapes and seeing what landed. Once I got two or three pieces to fit, then I was just drawing lines around there and it was slowly building into a larger thing. The first version of Palma was called the hand shape—palm and hand, it’s in the same family. How Hem and I worked on evolving the shape was making it more circular and a bit lighter.

You’ve been nominated for the Hublot Design Prize and were recently named one of 25 trailblazers leading the Design for Planet movement by the World Design Congress. Even with all the prestigious recognition that you’ve received, do you feel like you have community within the design world? I’m curious about what your experience has been like with networking and building relationships.

KM: The only person I will ever forever mention is Nifemi Marcus Bello, he’s like a brother. I met him when we did the Hublot Design Prize—we always knew of each other and supported each other’s work, but were never able to interact because he lives in Nigeria. Since then, I’ve leaned on him a lot for advice, he is a great sounding board. It’s quite hard because the design industry is very white and [full of] men; it’s a bit of a boys club, I’m tired of it. There are women who are doing their thing, but they’re focused on doing what they need to do to get where they need to go… In terms of community [in design], I don’t think I have one. I don’t make my own stuff [by hand] whereas a lot of other designers are making their own work, I’m just bringing to life what is in my brain. Maybe I get a bit relegated like that is what ties that community together in some way.

When I went to Milan [for Salone del Mobile/Milan Design Week], I found this really gorgeous company called Soft Witness and I messaged [Whitney Krieger] like “I loved seeing you there, can we link up?” I’ve been mothering for so long and I need to get back into a space where I’m also networking and creating and building. Half of it is you building it and half of it is there for you, but a lot of it is putting yourself out there. I’m really happy to put myself out there for others like myself to get where they need to go and if I’m going to be a stepping stone then fine, whatever. Maybe it’s just the cross I have to bear… Another person is Aiden Bowman from Trueing, I consider him like a mentor—he gave me funding during BLM and has always been there at pivotal points in my life, so I am super appreciative of his ear and his mind.

How has motherhood impacted your design practice?

KM: Legacy is really important for me, even if I’m not doing anything super important. I’m just making poufs, honestly. The fact that I’m making any impact on the design community as a Black woman is the most important thing because they’ll eventually have a step up. Now motherhood means I have less time. My truest passion is not this now—it’s definitely still a passion of mine, it’s not a side hustle, but I have to devote this time [to my children] first because I’ll never get this time back. That’s also sometimes what’s difficult, especially within the design community, because it’s filled with men.

The race we’re running isn’t the same because the women that have kids, if they’re working the hardest, they have no time. They’re juggling so much and need to get their feet in the doors, otherwise it feels like it’s going to go. It shouldn’t feel like that, it should feel like there’s space for everyone. But men get to do what they want to do even if they have kids. Our first loves are the kids and we make stuff work around that. I’m also thinking about communal space and how to better interact with one another because I don’t want my kids to be socially inept. I hope with a mother like me they’ll be talking to everybody!

What else can we expect from you in the year ahead?

KM: One of the things I’m trying to focus more on is not doing a lot of [private] commissioned work, I just want to be able to collaborate with companies like Hem and create products. On the side of my own practice and being an artist and designer is telling stories through textiles. That speaks so true to my heritage and who I am because there’s so much symbolism and storytelling in my own Ghanaian heritage. I want to be able to do something with that and tell my own story, so I think that’s what I’m going to be doing for the next year or two or three.

I’ve had a lot of identity changes becoming a mom and figuring out how to fit in. I’m making a purposeful effort to really build a community and not be complaining that there isn’t one. You can’t sit at home and then expect a network of people to come to you. I’m trying to do that for myself and as I’m trying to do that people are being receptive… I definitely am grateful for, much like yourself, the community outside of this [industry] who are somewhat creative but kind of oblivious to this [work]—it means I can dip in and dip out. It’s just hard when you need someone to actually fuse a connection together.